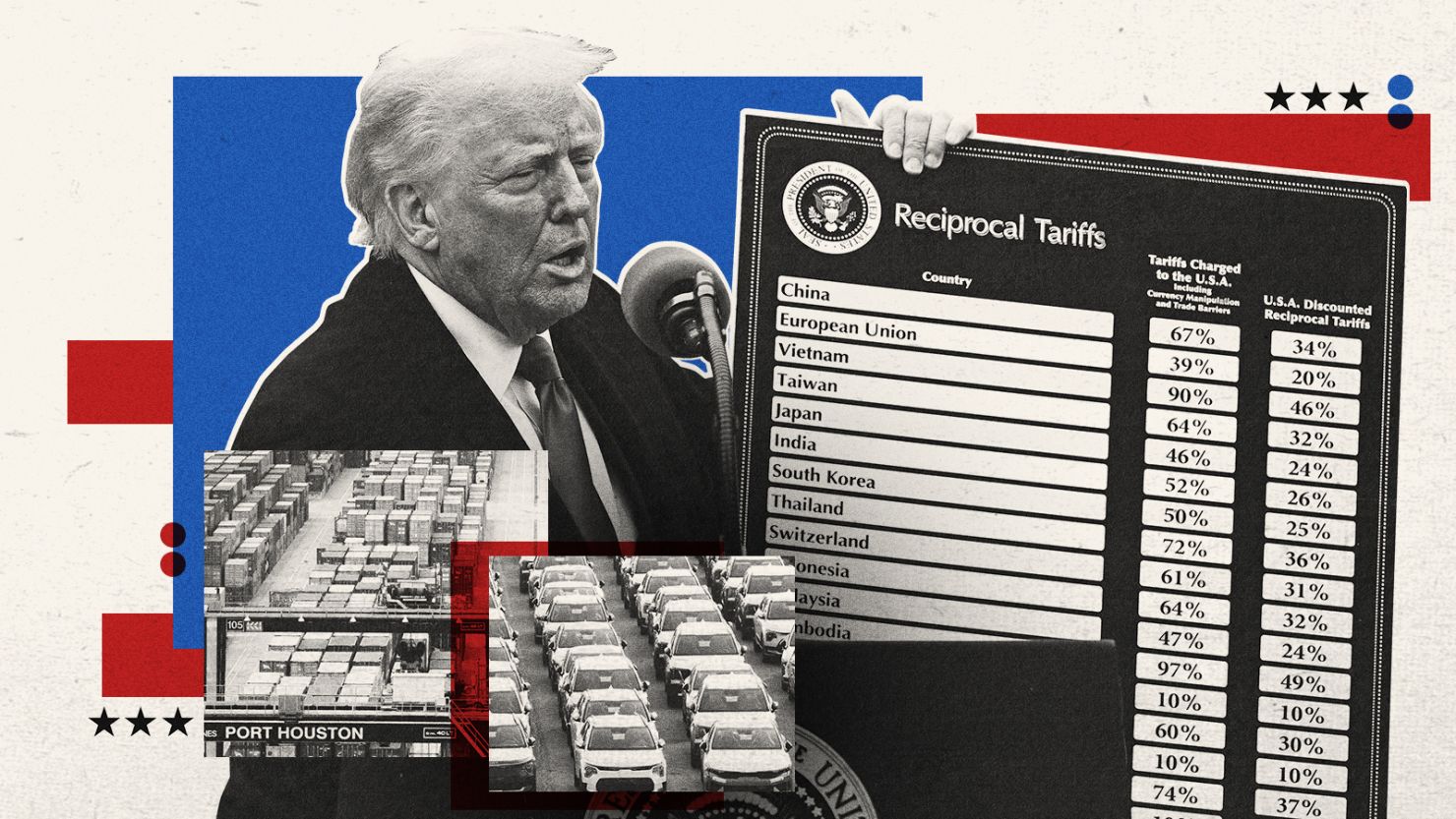

Tariffs are no longer a background detail in Caribbean trade. They now shape what moves, when it moves, and at what price.

For businesses that depend on shipping routes around the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, understanding how tariff policies work their way through supply chains is essential for planning, pricing, and long-term strategy.

This region is highly trade-oriented. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the simple average tariff across all products was 6.82 percent in 2023, while the trade-weighted average was 3.86 percent (Source: WITS/World Bank). That average hides the fact that certain categories of goods face much higher duties, and small economies with narrow import bases can be especially exposed when tariffs rise on only a handful of key items.

Within CARICOM states, most tariffs on extra-regional goods are set through a common external tariff. Commentaries note that CARICOM states apply rates that generally range from zero to about 20 percent on industrial goods, with higher bands for some agricultural and sensitive products (Source: region-specific trade analysis). At the same time, multilateral analysis shows that for small island developing states, many of them in the Caribbean, the trade-weighted average tariffs imposed by major partners have already increased from 0.2 percent to almost 7 percent in recent years (Source: UNCTAD). That is a major shift in a short period, and it is already changing freight flows.

Food trade illustrates the impact very clearly. Caribbean states import a large share of their food requirements, with U.S. and extra-regional production forming a big portion of that supply. When tariffs raise the cost of food entering the American market, or when input costs for U.S. producers increase, that can cascade into higher landed prices for Caribbean importers. For net food‐importing Caribbean states this means higher costs for everything from grain and meat to processed goods. When retail markets are small and competition is limited, the ability of wholesalers and supermarkets to absorb those increases is narrow - so price changes reach the consumer quickly.

Tariffs also affect energy and construction materials, which are central to development and tourism projects. Many Caribbean economies import fuel, steel, cement, and specialized equipment from North America, Europe, and increasingly from Asia. An increase in upstream tariffs on steel or aluminum in a major hub economy can ripple into higher costs for finished construction materials. These costs then appear in port fees, warehouse charges, and freight surcharges. Over time they contribute to higher project costs and can delay or scale down planned investments in hotels, housing, and infrastructure.

Tariffs are a complicated trade tool. Temporary revenues are often offset by decreased trade volume and reduced consumer demand. Manufacturors

Supply chains are also affected through timing, not just cost. When tariffs increase, they are often accompanied by stricter customs procedures, and more detailed inspections. Analysis of tariff threats toward the Caribbean notes that customs delays and tighter checks can slow the release of goods, especially where rules of origin and classification are contested (Source: Caribbean trade commentary). For importers, that can mean longer lead times, larger safety stock, and higher working capital requirements. For perishable goods such as refrigerated food items, it can mean spoilage risk and more pressure to secure reliable cold-chain logistics.

Recent policy proposals in the United States show how quickly shipping costs can be altered by a single measure. Caribbean regional leaders have warned that a new tariff or fee on Chinese-built ships docking in U.S. ports could add between USD 1,500 and USD 4,000 to the cost of importing a single container into the region (Source: regional shipping cost analysis). Another regional analysis suggests that shipping costs for some lanes could even double because of added fees of USD 1.5 million per vessel-call (Source: industry briefing). Even if the exact figures vary by port and contract, the direction is clear. When carriers face higher port charges or tariffs on their vessels, they either raise freight rates, reduce frequency, or redeploy ships away from marginal routes.

For Caribbean importers and exporters, that has several practical consequences. First, higher freight rates raise the landed cost of imported goods even when the tariff on the goods themselves is unchanged. Second, longer transit times or less frequent sailings force businesses to change ordering patterns and hold more inventory. Third, some smaller firms may be priced out of direct containerized imports and pushed back into using intermediaries, which reduces margin and control over timing.

Tariffs and trade frictions are also beginning to show up in trade volume statistics. In 2023, total exports from CARICOM countries were about USD 38.8 billion, down from USD 44.9 billion in 2022, a decline of about 13.6 percent (Source: OEC/CARICOM profile). That decline has multiple causes, including commodity price movements and post-pandemic adjustments, but higher trade barriers and uncertainty in major partner markets are among pressures on export volumes. Imports tell a similar story: Latin America and the Caribbean as a region imported more than USD 1.37 trillion in goods and services in the latest year, but did so with a negative merchandise trade balance and with about 49 percent of tariff lines duty-free (Source: WITS/World Bank). Duty-free access on part of the tariff schedule helps, yet when global tariffs rise on shipping inputs (ships, fuel) or on critical goods such as machinery and intermediate components, the overall cost of trade still climbs.

From the perspective of an exporter or a logistics provider, tariffs reshape business decisions at several nodes in the chain:

The broader effect on international sales is complex. Higher tariffs in destination markets can make Caribbean exports less competitive relative to goods from countries that enjoy preferential trade agreements or lower costs. At the same time, if large economies engage in tariff conflicts that raise their mutual trade barriers, Caribbean producers may find openings to supply niche products or serve as alternative sourcing locations. However, seizing those opportunities requires stable, affordable shipping and predictable border procedures, which tariffs can undermine.

For logistics providers and exporters serving the Caribbean and surrounding Gulf region, the practical takeaway is that tariff policy can no longer be treated as a distant policy item. It is now a central variable in route planning, contract design, and customer communication. Providers need to monitor tariff changes not only on the goods they move, but also on ships, fuel, and ports. They also need to inform customers about how these changes may affect lead times, pricing, and the viability of different service options.

At the same time, regional governments and trade bodies are working to mitigate some of the damage. Caribbean leaders have stressed that new tariffs imposed by major partners could raise consumer prices and hurt key sectors, calling for deeper regional cooperation and a renewed push for self-sufficiency in agriculture and manufacturing (Source: Caribbean leadership statements). Long-term efforts to reduce import dependence and develop regional value chains will help buffer the region from future tariff shocks, but those projects take time and capital.

In the near term, tariffs are likely to keep pushing up costs, stretching delivery times, and pressuring trade volumes for many Caribbean economies. Businesses that trade into and out of the region will need to adapt by diversifying suppliers, rethinking inventory strategies, and working closely with logistics partners who understand the evolving tariff landscape. In a world where trade barriers move quickly, the most resilient firms will be those that treat tariffs not as a static backdrop, but as a core part of their supply-chain strategy.